Although many people think of human flight as beginning with the aircraft in the early 1900s, in fact people had been flying repeatedly for more than 100 years.

The first generally recognized human flight took place in Paris in 1783. Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d'Arlandes went 8 km (5 miles) in a hot air balloon invented by the Montgolfier brothers. The balloon was powered by a wood fire, and was not steerable: that is, it flew wherever the wind took it.

Ballooning became a major "rage" in Europe in the late 18th century, providing the first detailed understanding of the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere.

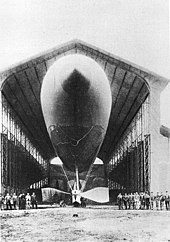

Work on developing a steerable (or dirigible) balloon (now called an airship) continued sporadically throughout the 1800s. The first powered, controlled, sustained lighter-than-air flight is believed to have taken place in 1852 when Henri Giffard flew 15 miles (24 km) in France, with a steam engine driven craft.

Non-steerable balloons were employed during the American Civil War by the Union Army Balloon Corps.

Another advance was made in 1884, when the first fully controllable free-flight was made in a French Army electric-powered airship, La France, by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs. The 170-foot (52 m) long , 66,000-cubic-foot (1,900 m3) airship covered 8 km (5 miles) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8½ horsepower electric motor.

However, these aircraft were generally short-lived and extremely frail. Routine, controlled flights would not come to pass until the advent of the internal combustion engine (see below.)

Although airships were used in both World War I and II, and continue on a limited basis to this day, their development has been largely overshadowed by heavier-than-air craft.

Heavier-than-air

Sustaining the aircraft

The first published paper on aviation was "Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air" by Emanuel Swedenborg published in 1716. This flying machine consisted of a light frame covered with strong canvas and provided with two large oars or wings moving on a horizontal axis, arranged so that the upstroke met with no resistance while the downstroke provided lifting power. Swedenborg knew that the machine would not fly, but suggested it as a start and was confident that the problem would be solved. He said, "It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come some one might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg." Swedenborg would prove prescient in his observation that powering the aircraft through the air was the crux of flying.During the last years of the 18th century, Sir George Cayley started the first rigorous study of the physics of flight. In 1799 he exhibited a plan for a glider, which except for planform was completely modern in having a separate tail for control and having the pilot suspended below the center of gravity to provide stability, and flew it as a model in 1804. Over the next five decades Cayley worked on and off on the problem, during which he invented most of basic aerodynamics and introduced such terms as lift and drag. He used both internal and external combustion engines, fueled by gunpowder. Later Cayley turned his research to building a full-scale version of his design, first flying it unmanned in 1849, and in 1853 his coachman made a short flight at Brompton, near Scarborough in Yorkshire.

In 1848, John Stringfellow had a successful indoor test flight of a steam-powered model, in Chard, Somerset, England.

In 1866 a Polish peasant, sculptor and carpenter by the name of Jan Wnęk built and flew a controllable glider. Wnęk was illiterate and self-taught, and could only count on his knowledge about nature based on observation of birds' flight and on his own builder and carver skills. Jan Wnęk was firmly strapped to his glider by the chest and hips and controlled his glider by twisting the wing's trailing edge via strings attached to stirrups at his feet. Church records indicate that Jan Wnęk launched from a special ramp on top of the Odporyszów church tower; The tower stood 45 m high and was located on top of a 50 m hill, making a 95 m (311 ft) high launch above the valley below. Jan Wnęk made several public flights of substantial distances between 1866 and 1869, especially during religious festivals, carnivals and New Year celebrations. Wnęk left no known written records or drawings, thus having no impact on aviation progress. Recently, Professor Tadeusz Seweryn, director of the Kraków Museum of Ethnography, has unearthed church records with descriptions of Jan Wnęk's activities.

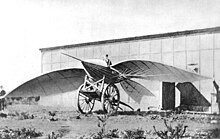

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first flight higher than his point of departure, by having his glider "L'Albatros artificiel" pulled by a horse on a beach. He reportedly achieved a height of 100 meters, over a distance of 200 meters.

Francis Herbert Wenham built a series of unsuccessful unmanned gliders. He found that the most of the lift from a bird-like wing appeared to be generated at the front edge, and concluded correctly that long, thin wings would be better than the bat-like ones suggested by many, because they would have more leading edge for their weight. Today this measure is known as aspect ratio. He presented a paper on his work to the newly formed Aeronautical Society of Great Britain in 1866, and decided to prove it by building the world's first wind tunnel in 1871. Members of the Society used the tunnel and learned that cambered wings generated considerably more lift than expected by Cayley's Newtonian reasoning, with lift-to-drag ratios of about 5:1 at 15 degrees. This clearly demonstrated the ability to build practical heavier-than-air flying machines; what remained was the problem of controlling the flight and powering them.

Around 1871 Alphonse Pénaud made rubber powered model aircraft. While of little direct practical use they inspired a whole generation of future flight pioneers, including the Wright brothers who were given them as toys as children.

In 1874, Félix du Temple built the "Monoplane", a large plane made of aluminium in Brest, France, with a wingspan of 13 meters and a weight of only 80 kilograms (without the driver). Several trials were made with the plane, and it is generally recognized that it achieved lift off under its own power after a ski-jump run, glided for a short time and returned safely to the ground, making it the first successful powered flight in history, although the flight was only a short distance and a short time.

Controlling the flight

The 1880s became a period of intense study, characterized by the "gentleman scientists" who represented most research efforts until the 20th century. Starting in the 1880s advancements were made in construction that led to the first truly practical gliders. Three people in particular were active: Otto Lilienthal, Percy Pilcher and Octave Chanute. One of the first truly modern gliders appears to have been built by John J. Montgomery; it flew in a controlled manner outside of San Diego on August 28, 1883. It was not until many years later that his efforts became well known. Another delta hang-glider had been constructed by Wilhelm Kress as early as 1877 near Vienna.Otto Lilienthal of Germany duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1874, publishing his research in 1889. He also produced a series of ever-better gliders, and in 1891 was able to make flights of 25 meters or more routinely. He rigorously documented his work, including photographs, and for this reason is one of the best known of the early pioneers. He also promoted the idea of "jumping before you fly", suggesting that researchers should start with gliders and work their way up, instead of simply designing a powered machine on paper and hoping it would work. His type of aircraft is now known as a hang glider.

By the time of his death in 1896 he had made 2500 flights on a number of designs, when a gust of wind broke the wing of his latest design, causing him to fall from a height of roughly 56 ft (17 m), fracturing his spine. He died the next day, with his last words being "small sacrifices must be made". Lilienthal had been working on small engines suitable for powering his designs at the time of his death.

Australian Lawrence Hargrave invented the box kite and dedicated his life to constructing flying machines. In the 1880s he experimented with monoplane models and by 1889 Hargrave had constructed a rotary airplane engine, driven by compressed air.

Picking up where Lilienthal left off, Octave Chanute took up aircraft design after an early retirement, and funded the development of several gliders. In the summer of 1896 his troop flew several of their designs many times at Miller Beach, Indiana, eventually deciding that the best was a biplane design that looks surprisingly modern. Like Lilienthal, he heavily documented his work while photographing it, and was busy corresponding with like-minded hobbyists around the world. Chanute was particularly interested in solving the problem of aerodynamic instability of the aircraft in flight, one which birds corrected for by instant corrections, but one that humans would have to address with stabilizing and control surfaces (or moving center of gravity, as Lilienthal did). The most disconcerting problem was longitudinal instability (divergence), because as the angle of attack of a wing increased, the center of pressure moved forward and made the angle increase more. Without immediate correction, the craft would pitch up and stall. Much more difficult to understand was the mixing of lateral/directional stability and control.

Powering the aircraft

Throughout this period, a number of attempts were made to produce a true powered aircraft. However the majority of these efforts were doomed to failure, being designed by hobbyists who did not have a full understanding of the problems being discussed by Lilienthal and Chanute.In France Clément Ader built the steam-powered Eole and may have made a 50-meter flight near Paris in 1890, which would be the first self-propelled "long distance" flight in history. Ader then worked on a larger design which took five years to build. In a test for the French military, the Avion III reportedly managed to cover 300 meters at a very small height, crashing out of control.

In 1884, Alexander Mozhaysky's monoplane design made what is now considered to be a power assisted take off or 'hop' of 60–100 feet (20–30 meters) near Krasnoye Selo, Russia.

Sir Hiram Maxim studied a series of designs in England, eventually building a monstrous 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) design with a wingspan of 105 feet (32 m), powered by two advanced low-weight steam engines which delivered 180 hp (134 kW) each. Maxim built it to study the basic problems of construction and power and it remained without controls, and, realizing that it would be unsafe to fly, he instead had a 1,800 foot (550 m) track constructed for test runs. After a number of test runs working out problems, on July 31, 1894 they started a series of runs at increasing power settings. The first two were successful, with the craft "flying" on the rails. In the afternoon the crew of three fired the boilers to full power, and after reaching over 42 mph (68 km/h) about 600 ft (180 m) down the track the machine produced so much lift it pulled itself free of the track and crashed after flying at low altitudes for about 200 feet (60 m). Declining fortunes left him unable to continue his work until the 1900s, when he was able to test a number of smaller designs powered by gasoline.

In the United Kingdom an attempt at heavier-than-air flight was made by the aviation pioneer Percy Pilcher. Pilcher had built several working gliders, The Bat, The Beetle, The Gull and The Hawk, which he flew successfully during the mid to late 1890s. In 1899 he constructed a prototype powered aircraft which, recent research has shown, would have been capable of flight. However, he died in a glider accident before he was able to test it, and his plans were forgotten for many years.

No comments:

Post a Comment