.

The first form of man-made flying objects were kites.The earliest known record of kite flying is from around 200 B.C. in China, when a general flew a kite over enemy territory to calculate the length of tunnel required to enter the region. Yuan Huangtou, a Chinese prince, survived by tying himself to the kite.Leonardo da Vinci's (15th c.) dream of flight found expression in several designs, but he did not attempt to demonstrate flight by literally constructing them.

With the efforts to analyze the atmosphere in the 17th and 18th century, gases such as hydrogen were discovered which in turn led to the invention of hydrogen balloons. Various theories in mechanics by physicists during the same period of time—notably fluid dynamics and Newton's laws of motion—led to the foundation of modern aerodynamics. Tethered balloons filled with hot air were used in the first half of the 19th century and saw considerable action in several mid-century wars, most notably the American Civil War, where balloons provided observation during the Battle of Petersburg.

Experiments with gliders laid a groundwork to build heavier-than-air crafts, and by the early 20th century advancements in engine technology and aerodynamics made controlled, powered flight possible for the first time.

Mythology

Human ambition to fly is illustrated in mythological literature of several cultures; the wings made out of wax and feathers by Daedalus in Greek mythology, or the Pushpaka Vimana of king Ravana in Ramayana, for instance.Flight automaton in Greece

Around 400 B.C., Archytas, the Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman and strategist, designed and built a bird-shaped, apparently steam powered model named "The Pigeon" (Greek: Περιστέρα "Peristera"), which is said to have flown some 200 meters.According to Aulus Gellius, the mechanical bird was suspended on a string or pivot and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".Hot air balloons and kites in China

The Kongming lantern (proto hot air balloon) was known in China from ancient times. Its invention is usually attributed to the general Zhuge Liang (180–234 AD, honorific title Kongming), who is said to have used them to scare the enemy troops:An oil lamp was installed under a large paper bag, and the bag floated in the air due to the lamp heating the air. ... The enemy was frightened by the light in the air, thinking that some divine force was helping him.

However, the device based on a lamp in a paper shell is documented earlier, and according to Joseph Needham, hot-air balloons in China were known from the 3rd century BC.

In the 5th century BCE Lu Ban invented a 'wooden bird' which may have been a large kite, or which may have been an early glider.

During the Yuan dynasty (13th c.) under rulers like Kublai Khan, the rectangular lamps became popular in festivals, when they would attract huge crowds. During the Mongol Empire, the design may have spread along the Silk Route into Central Asia and the Middle East. Almost identical floating lights with a rectangular lamp in thin paper scaffolding are common in Tibetan celebrations and in the Indian festival of lights, Diwali. However, there is no evidence that these were used for human flight.

Gliders in Europe

Between 1000 and 1010, the English Benedictine monk Eilmer of Malmesbury flew for about 200 meters using a glider (circa 1010), but sustained injuries, too. The event is recorded in the work of the eminent medieval historian William of Malmesbury in about 1125.Being a fellow monk in the same abbey, William almost certainly obtained his account directly from people there who knew Eilmer himself.

From Renaissance to the 18th century

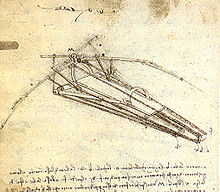

Some six centuries after Ibn Firnas, Leonardo da Vinci developed a hang glider design in which the inner parts of the wings are fixed, and some control surfaces are provided towards the tips (as in the gliding flight in birds). While his drawings exist and are deemed flightworthy in principle, he himself never flew in it. Based on his drawings, and using materials that would have been available to him, a prototype constructed in the late 20th century was shown to fly. However, his sketchy design was interpreted with modern knowledge of aerodynamic principles, and whether his actual ideas would have flown is not known. A model he built for a test flight in 1496 did not fly, and some other designs, such as the four-person screw-type helicopter have severe flaws.In 1670 Francesco Lana de Terzi published work that suggested lighter than air flight would be possible by having copper foil spheres that contained a vacuum that would be lighter than the displaced air, lift an airship (rather literal from his drawing). While not being completely off the mark, he did fail to realize that the pressure of the surrounding air would smash the spheres.

In 1709, Bartolomeu de Gusmão presented a petition to King John V of Portugal, begging a privilege for his invention of an airship, in which he expressed the greatest confidence. The public test of the machine, which was set for June 24, 1709, did not take place. According to contemporary reports, however, Gusmão appears to have made several less ambitious experiments with this machine, descending from eminences. It is certain that Gusmão was working on this principle at the public exhibition he gave before the Court on August 8, 1709, in the hall of the Casa da Índia in Lisbon, when he propelled a ball to the roof by combustion.

No comments:

Post a Comment